RPG: The Legacy Of The Open Gaming License – PRIME

In the year 2000, three letters set off a revolution in an industry that itself was only three letters (RPG). The OGL changed the face of gaming. Here’s how.

The OGL, or Open Gaming License, changed the face of the tabletop roleplaying game industry back in the distant, innocent days of the year 2000. With a new millennium on the horizon and a newly minted edition of Dungeons & Dragons lighting the way, the Open Gaming License opened the door to a slew of 3rd-party creators in a way few were anticipating. Companies waxed and waned under its influence–Paizo and Pathfinder only exist today because of it–and when it was good, it was really good. When it was bad, it was really bad. The Open Gaming License ushered in a whole new era.

Journey with us to the past, to the year 2000. A simpler time when Conan O’Brien was a late-night talk show host, webcomics like User Friendly and Sluggy Freelance were updating regularly, Marvel movie franchises (like X-Men) were making money hand over fist for movie studios, and the RPG was experiencing a huge surge in popularity thanks to the latest edition of Dungeons & Dragons. Wait… all of that is still happening? Next you’ll be telling me there’s another Matrix Movie in the works and everyone’s getting hyped for it.

Why even bother having time if everything’s just going to stay the same. Alright, so we’ve proven that time is a flat circle, but let’s take a look at one particular moment in history: the advent of the Open Gaming License. Back in 2000, which is basically the present day but worse because they didn’t have iPhones yet, D&D 3rd Edition was newly minted and it was taking off like a rocket.

In 2000, the d20 would go on to become its own market, which I say to help you understand just how much of the industry D&D represents. It’s basically the continental shelf upon which the tabletop rpg industry stands. Look back at ICv2’s recounting of the numbers and you’ll find D&D is the top pretty consistently with a few notable exceptions–but even those come down to the OGL–and it’s only the continuing of a trend that began after Wizards of the Coast rescued a troubled TSR with D&D 3rd Edition.

3rd Edition did more than just revise the rules of D&D. It launched the d20 Trademark License and Open Gaming License, which opened the doors for anyone to publish D&D and D&D accessories using the d20 brand, effectively turning the d20 system into an RPG engine that other people could use to power their games, much like Epic Games did with their Unreal Engine just a few years earlier. And much like the Unreal Engine enabled more games to be created, the d20 System saw the creation of a new kind of company–one dedicated to publishing d20 content.

Three companies hit the ground running with their own D&D adventures ready to go on 3E Launch Day: Green Ronin with Death in Freeport, Atlas Games with Three Days to Kill and Necromancer Games with The Wizard’s Amulet. But these were hardly the only ones out there. The first few years of the aughts were a veritable d20 boom. Companies could make or break themselves on how quickly they could adapt to the change to the market. Green Ronin, for instance, started as just another RPG publisher, but quickly adapted to the d20 market and earned a spot at the top. How was all this possible? Well, let’s take a look at the Open Gaming License itself.

The Open Gaming License

Put forth in 2000 by Ryan Dancey, one of the folks that spearheaded the acquisition of TSR by Wizards of the Coast, the Open Gaming License is a short document that outlines how you can use the “Open Gaming Content.” Here’s a snippet:

1. Definitions: (a)”Contributors” means the copyright and/or trademark owners who have contributed Open Game Content; (b)”Derivative Material” means copyrighted material including derivative works and translations (including into other computer languages), potation, modification, correction, addition, extension, upgrade, improvement, compilation, abridgment or other form in which an existing work may be recast, transformed or adapted; (c) “Distribute” means to reproduce, license, rent, lease, sell, broadcast, publicly display, transmit or otherwise distribute; (d)”Open Game Content” means the game mechanic and includes the methods, procedures, processes and routines to the extent such content does not embody the Product Identity and is an enhancement over the prior art and any additional content clearly identified as Open Game Content by the Contributor, and means any work covered by this License, including translations and derivative works under copyright law, but specifically excludes Product Identity. (e) “Product Identity” means product and product line names, logos and identifying marks including trade dress; artifacts; creatures characters; stories, storylines, plots, thematic elements, dialogue, incidents, language, artwork, symbols, designs, depictions, likenesses, formats, poses, concepts, themes and graphic, photographic and other visual or audio representations; names and descriptions of characters, spells, enchantments, personalities, teams, personas, likenesses and special abilities; places, locations, environments, creatures, equipment, magical or supernatural abilities or effects, logos, symbols, or graphic designs; and any other trademark or registered trademark clearly identified as Product identity by the owner of the Product Identity, and which specifically excludes the Open Game Content; (f) “Trademark” means the logos, names, mark, sign, motto, designs that are used by a Contributor to identify itself or its products or the associated products contributed to the Open Game License by the Contributor (g) “Use”, “Used” or “Using” means to use, Distribute, copy, edit, format, modify, translate and otherwise create Derivative Material of Open Game Content. (h) “You” or “Your” means the licensee in terms of this agreement.

2. The License: This License applies to any Open Game Content that contains a notice indicating that the Open Game Content may only be Used under and in terms of this License. You must affix such a notice to any Open Game Content that you Use. No terms may be added to or subtracted from this License except as described by the License itself. No other terms or conditions may be applied to any Open Game Content distributed using this License.

The most relevant part is that the OGL splits D&D into two distinct parts: “open gaming content” which is free to use–and it’s worth pointing out things like rules and mechanics aren’t copyrightable in the first place, and things like formatting or stat blocks are in dispute even to this day–and “Product Identity” which are things like Mind Flayers and named characters and the Forgotten Realms. This is when D&D took its first steps into the modern world, going open-source as the rest of the world started catching up to movies like Hackers and The Net.

This led to the creation of the System Reference Document or SRD which might be familiar to some of you. It also led to a change in the way that D&D, and the people behind it, saw the game and in no small part leads to the emphasis on the D&D Community that is behind the massive surge in popularity right now. Dancey–and the staff at WotC, as well as a number of enthusiastic community supporters and folks we don’t really see (after all, the Great Man theory of history is a piece of colonial hogwash so outdated even spiders are dunking on it)–believed that the true strength of D&D was the friends we made along the way. Where TSR had been far too aggressive looking for various copyright violations and lawsuits as a way of slapping down competitors, a move that never ends well, as certain other gaming companies would go on to learn, WotC’s D&D was much more open to the community.

The System Reference Document was designed to get the community talking about D&D, thinking about it, and using it for whatever they could think of. And by and large, this worked.

You would, in general, see three kinds of d20 content. Adventure modules, system hacks, and splatbooks. Adventure modules are fairly obvious, and probably one of the easiest to make. These are adventures that weren’t published by WotC but were fully compatible with the rules. They made use of the same formatting, the same stats, used the same publicly available monsters (more on that in a moment) and are basically the same sorts of things you can still find today.

System hacks are different interpretations of the d20 Engine, adapting it away from the 3E system to get a different flavor of game. This led in part to the Old School Renaissance (OSR) where people would modify 3rd Edition to try and evoke the elder days of D&D’s Basic or eXpert or Master systems with folks like Goodman Games releasing Dungeon Crawl Classics. But you’d also see games like Vampire the Masquerade, Mutants and Masterminds, Alternity, WotC’s own future RPG system, or Spycraft, even the swashbuckling 7th Sea saw a brief, furtive existence as a d20 system title.

Finally, splatbooks. These are supplements for D&D proper, but not published by WotC. Things like Mongoose Publishing’s Quintessential Guides or Green Ronin’s Races of Renown fall under this category. There were plenty of these as well.

And it worked. From 2001 and on, there was a veritable explosion of d20 content. It’s a case of the right tools at the right time–the community was ready, and hungry, for more games. Thanks to the internet they could get shared around much more readily; this is the same era in which .pdf publishing allowed indie publishers to take advantage of lower overhead costs, to get their product out in front of more eyes than ever before. It was the gold rush of the internet.

And people were staking out their claims. But, as was popular in the 3-year-old Behind the Music franchise… suddenly it all came crashing down. Actually, it would come crashing down a few times, but let’s take a look at the first crash, which comes just three years into things, with the shift from 3rd Edition to 3.5. It’s easy to forget how different the two versions are–even going back through the books, most of what I recall from the 3.x days are changes that 3.5 made and locked in. In many ways, 3.5 is the D&D ruleset that went on to found things… to the detriment of many publishers who had stocks full of now obsolete 3.0 materials.

Sure you could convert modules, but by and large, if you’re buying something you want something that already works with the game you’re playing. And players had pretty much universally embraced 3.5 edition’s rules, which meant that the d20 System had already shown some of its cracks. The gaming industry was hit hard–companies continued on, but had to keep themselves light. Published copies dropped off in favor of .pdfs, though you still saw swaths of new games.

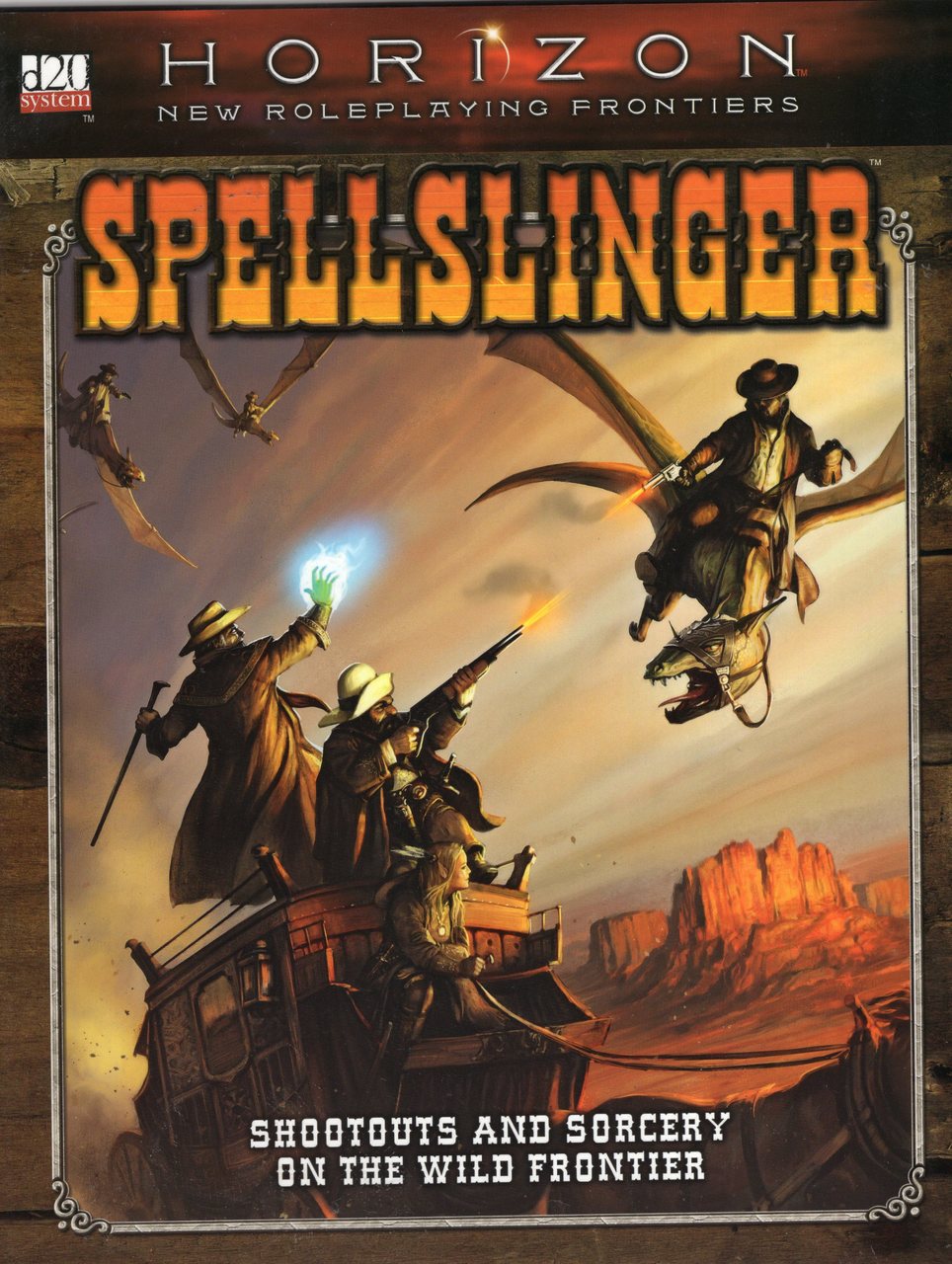

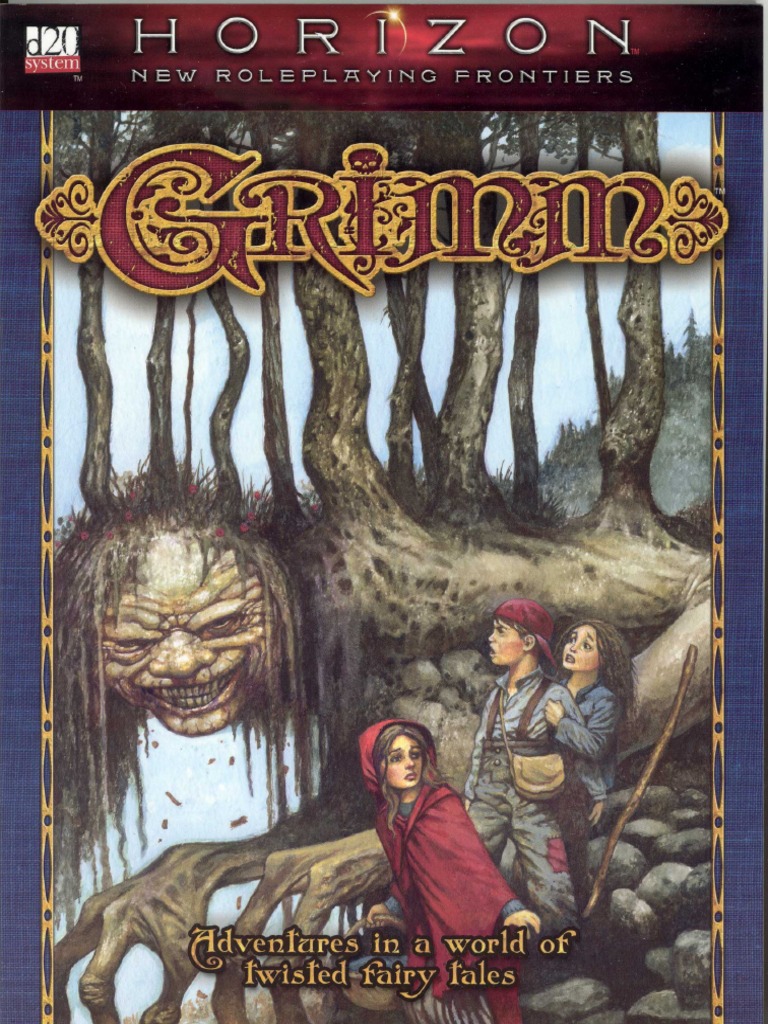

I recall playing through two, both by Horizon: Spellslinger, a fantasy/western mashup that remains one of my favorite campaigns to this day even if we did all die, and Grimm, which went on to have its own independent game developed. Grimm is a game of fairy tale adventures where you play as Children who stumble into the world of the Brothers Grimm’s tales and find yourself contending with creatures that you’re meant to outsmart or outrun rather than take head-on in a fight every time. It’s a ton of fun and definitely worth checking out…

But those came outpost 3.5 transition. And what a time that was. 3.5 and its updated OGL were more refined, and coming out as they did in 2004 they coincided with a rising love of Steampunk. While it might have hit its heyday in the late 2000s, even this trend has its role in the ripples cast out by the OGL. Let’s talk about a company who exists now because they got their start as a d20 publisher that would go on to create an iconic world in which a loyal fanbase of gamers would come to find a home away from D&D. I’m talking, of course, about Privateer Press.

Privateer’s first few titles were d20 adventures collectively known as The Witchfire Trilogy. These adventures painted the world of the Iron Kingdoms, a steampunk setting that mixed fantasy and steam and gunpowder to create the world of the miniatures game which has come to exemplify their company. That’s right, Warcasters, Warjacks, Infernals, Hordes, even Privateer’s love for “Lock and Load” have their origins in D&D and the OGL. Lock and Load, in fact, was first a character primer for the Iron Kingdoms published in 2002. But as the change to 3.5 edition hit, Privateer Press was in a fantastic position. They leveraged their success with d20 content and their IP of the Iron Kingdoms into Warmachine, which would go on to carve out a niche in the non-collectible miniatures market. From there it’s all Monsterpocalypse, Hordes, and Oblivion, so it seems like things have worked out well for them.

Most RPG companies that are around today have some contact with the OGL, though. Let’s talk about another company that grew out of the shaky grounds of the early 2000s and blossomed into their own. Now we’re talking about Paizo, which owes its existence to D&D, and its success to D&D 4th Edition. Plus a number of other things. Again, history is made up of a ton of events and there’s no single one thing that influences anything, you only can construct a narrative after the fact, and if you try and get a sense of what’s actively happening it’s like staring into a hurricane where all the constituent drops of rain are just trying to figure out how to put food on the table and take Karen to soccer practice because she’s been moping around ever since you changed schools. Which is to say, history is a little absurd as it unfolds, but you can piece together meaning after the fact.

So it is with Paizo, which began life with D&D’s magazines, Dungeon and Dragon. In 2002, Paizo Publishing was formed to take advantage of the newly passed on publishing license. Paizo published Dungeon and Dragon as well as Star Wars Insider, a Star Wars fan club magazine. Dungeon magazine, in particular, led to the birth of Pathfinder. Paizo’s earliest history was the creation of “adventure paths” for Dungeon magazine. These were linked adventures that were published regularly in the magazine with The Shackled City, which kicked off a 12-part adventure that took characters from 1st-20th level. The same would go for the Age of Worms and Savage Tides. These paths were massively popular. Paizo was able to create epic adventures in the pages of Dungeon, and because they were working so closely with 3.x through the OGL, they could support the editions even better than most.

Right up until Wizards reclaimed the licenses for the magazines, and ended the print runs of the magazines in 2007. Dungeon #359 and Dragon #150 are the final print issues of these venerable titles. All of this was in advance of preparation for 4th Edition, which would be announced at that year’s GenCon. Paizo, meanwhile had been developing their own world under the OGL, rather than as a d20 System product–meaning their world of Golarion had to stand on its own with the open gaming content.

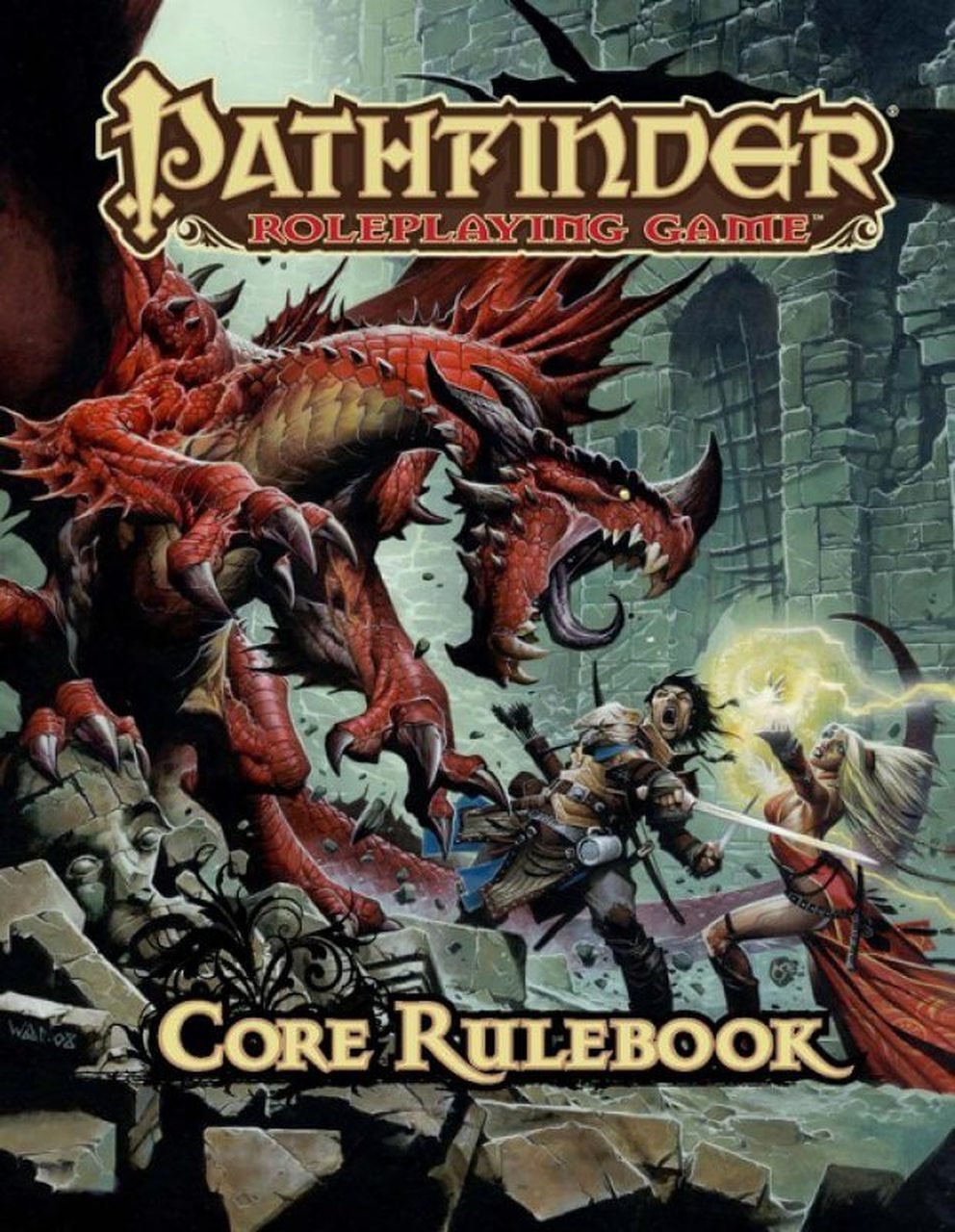

It also meant that when Wizards decided to revoke the OGL with 4th Edition–a move that gutted the industry and led to the second big crash we mentioned earlier–in favor of a new, more restrictive Gaming System License, Paizo could continue on with Pathfinder. And that’s where Pathfinder is born. Affectionately called D&D 3.75 by its loyal fans at the beginning, the Pathfinder RPG took off, launching ten years ago in 2009 to massive fanfare. Especially since the new game was largely compatible with the old 3.5 material, meaning that players could still use most of their old books if they went with Pathfinder, as opposed to D&D’s 4th Edition, which was a massive pivot from 3.x.

For a while Pathfinder managed to overtake D&D–an interesting statement considering that it was born of the OGL–but eventually 5th Edition would come out and a whole new ‘new era’ would be ushered in. But that’s a story for another time. For now, it’s enough to know that the OGL gave Pathfinder a massive foothold in a market that previously had been dominated by the shadow of one massive company.

In the current day, things feel much more open. D&D 5th Edition has returned to the OGL, offering up a new System Reference Document, as well as promoting their own marketplace for community-created content: the DM’s Guild. With a program designed to find new and promising writers/designers/artists, they have a pool to pick from for new content and to highlight folks as community leaders. Again, it comes back to the community.

But it’s not just D&D. Other games have embraced this principle. Apocalypse World and Blades in the Dark are two who have found prominent success in the industry. But a whole sprawling community of indie RPG designers found their home on Google+ of all places, and you’d see more hacks and conversions and modded variations of games get passed around. Sadly that vanished earlier this year when Google+ shut down in April. That community spirit remains invested in gaming.

It’s shades of the same stories you hear about the development of the original D&D. People would play games, try things, see what worked, and then find ways to share their discoveries. And there’s a kind of elegance in that–and not just because 1974 was also a year for corrupt politicians, proving that history is nothing if not consistent–but in a game that you can’t play without a community of friends, a community ends up being what keeps it going even through hard times.

I guess what I’m saying is, the real OGL is the friends we made along the way.