How D&D Changed Video Games: From Ultima To JRPGs And Beyond – Prime

What does D&D have to do with an eccentric billionaire, a beloved series of Japanese novels, and the video games you love today? More than you’d think…

D&D and video games seem to go hand in hand–terms like hit points/health and AC help illustrate this, but even more elementary parts of video games come from D&D’s influence. Things like Boss Fights and NPC allies/pets all have their origins in D&D’s influence over the early days of video games. As we learned in our last article, looking at the early early days, when video games were illicitly programmed and shared over the mainframe computers of universities throughout the world, like something you’d expect to read in the background of a cyberpunk hero, D&D was a huge influence. Games like pedit5 and dnd took the ideas presented in D&D and adapted them into games where they took on a life of their own.

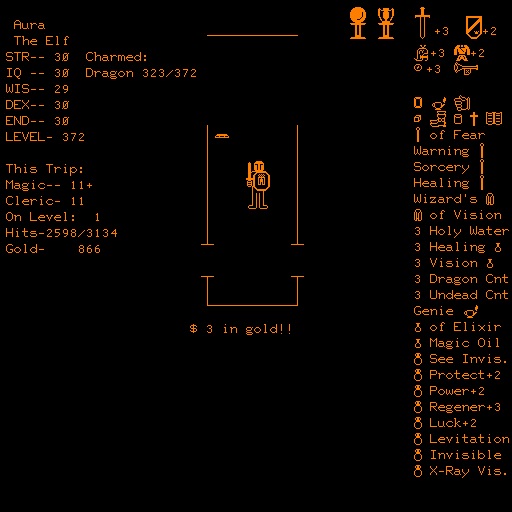

pedit5 laid out randomly-generated monster encounters and treasure in a fixed-map dungeon which players would tackle with a single character they created using many of the same statistics of D&D. This game had a great deal of influence on other games like dnd, which famously introduced many of the features we pretty much take for granted in video games today. If you’ve ever repeatedly died at the hands of Father Gascoigne, or permanently fused your hand into a claw trying to play Through the Fire and the Flames on Expert at the end of Guitar Hero you’ve run up against a concept introduced (as far as anyone can tell) in the game of dnd.

Gascoigne here is attempting to 100% the song as we speak

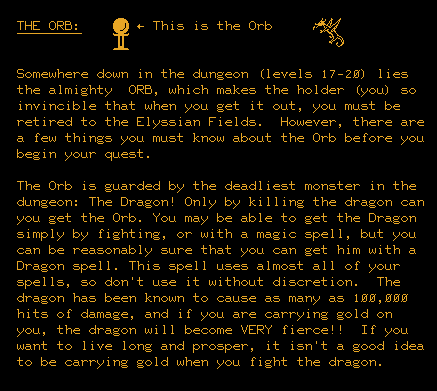

dnd took the idea of a dungeon crawl from D&D and put players in command of a party of characters, sent them into a dungeon to retrieve a magical Orb and invented things like teleporters along the way:

As we built the game we added new features that we didn’t see in other games, such as the Orb, transporters, the idea of a boss monster (there was no term for that since there wasn’t anything remotely like that at the time, we just wanted a final challenge against a very powerful opponent before you could “win” the game and have your character retired to the Elysian Fields).

Dirk Pellett had also played D&D at Caltech in 1974 and 1975, before coming to Iowa State University. He played dnd, and liked the game so much that he had ideas for improving it. He made his suggestions to the original authors, Gary Whisenhunt and Ray Wood. They liked his ideas enough to give him access to edit the game directly, and he joined them as a full-fledged author of the game. By October 30th, 1976, Dirk had added many enhancements, including a great variety of magic items and more monster types. Within 21 months of the publication of the D&D rule book, the game of dnd based on it had reached version 2.8, and a counter of the number of dungeon trips by all players since the game’s creation (or, at least, since the counter was initialized) was fast approaching the 100,000th trip.

Advertisement

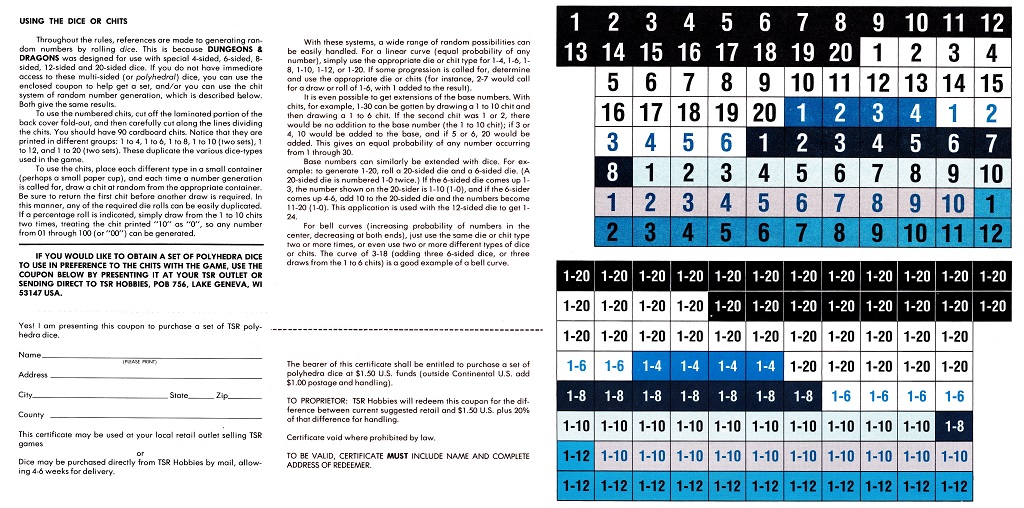

And all of this happened just 21 months after the release of D&D, as it was spreading rapidly across the country in certain nerdy circles. It hadn’t quite reached the levels of popularity that would see the game cause a shortage of dice for a while, resulting in a disastrous run of “random number chits” that stood in for the satisfying roll of a d20, because the manufacturers of the dice simply couldn’t keep up with the demand for the dice being packaged with the D&D boxed set.

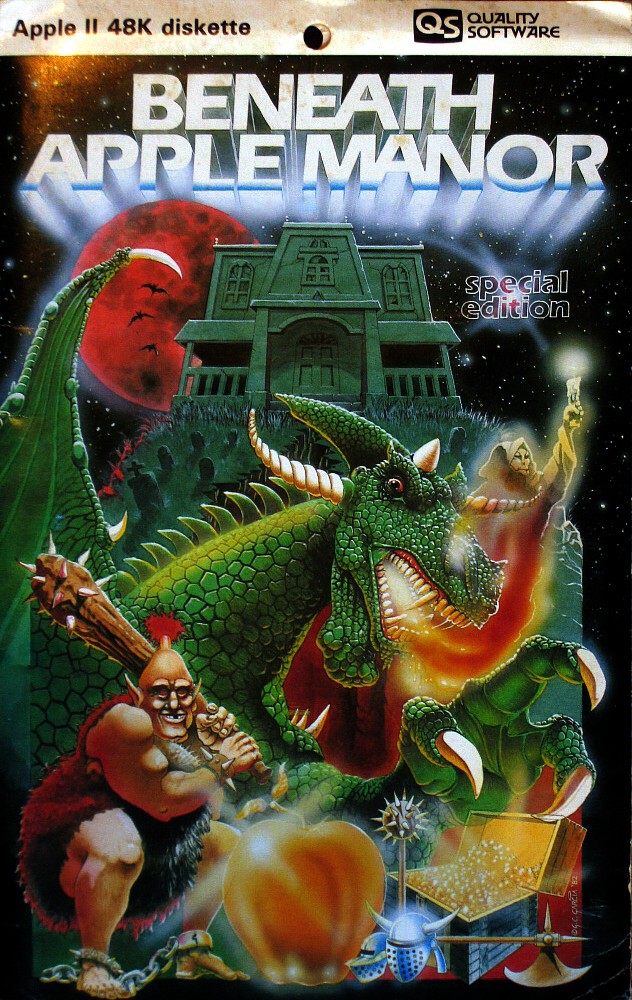

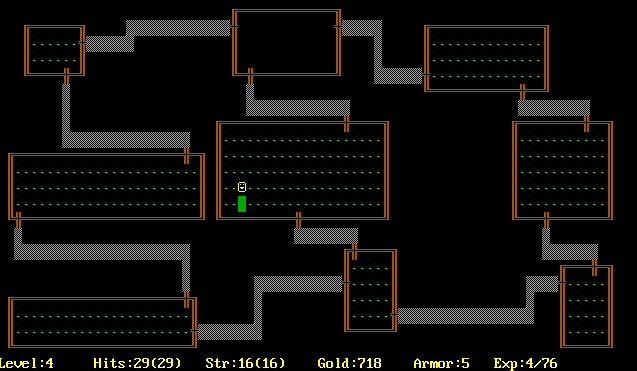

We’ve already seen how D&D helped spawn the text adventure genre, with a look at how both caving and a love of D&D came together in one of the earliest pieces of interactive fiction, Colossal Cave Adventure which would go on to inspire Zork. And in the origins of pedit5 and dnd and an accounting of a short-lived game for the PDP-10 by Don Daglow, Dungeon–a fully functioning fantasy RPG that featured “both ranged and melee combat, lines of sight, auto-mapping and NPC’s with discrete AI,”–we can see the inspiration for a whole other genre of games, Roguelikes. Games like Moria and Avatar came shortly after Dungeon and dnd, which all sort of culminate in 1978 and the Apple II and the game Beneath Apple Manor. The game, called BAM for short, was developed by Don Worth for the Apple II and is the first known instance of a game that we’d recognize as a roguelike. Right down to its graphics and everything:

In Apple Manor, you are sent into the titular manor to find a magical golden apple, which lies in the dungeon beneath the house. Though the main mission was simple, the gameplay itself was anything but, and it once again, all comes back to Dungeons and Dragons:

Outside the computer lab and away from their homemade space-faring game, Worth and his buddies played Dungeons & Dragons. They immersed themselves in the fantasy of exploring strange places, unearthing fantastic treasures, and rolling dice to determine whether their intrepid party of programmers-turned-adventurers lived or perished.

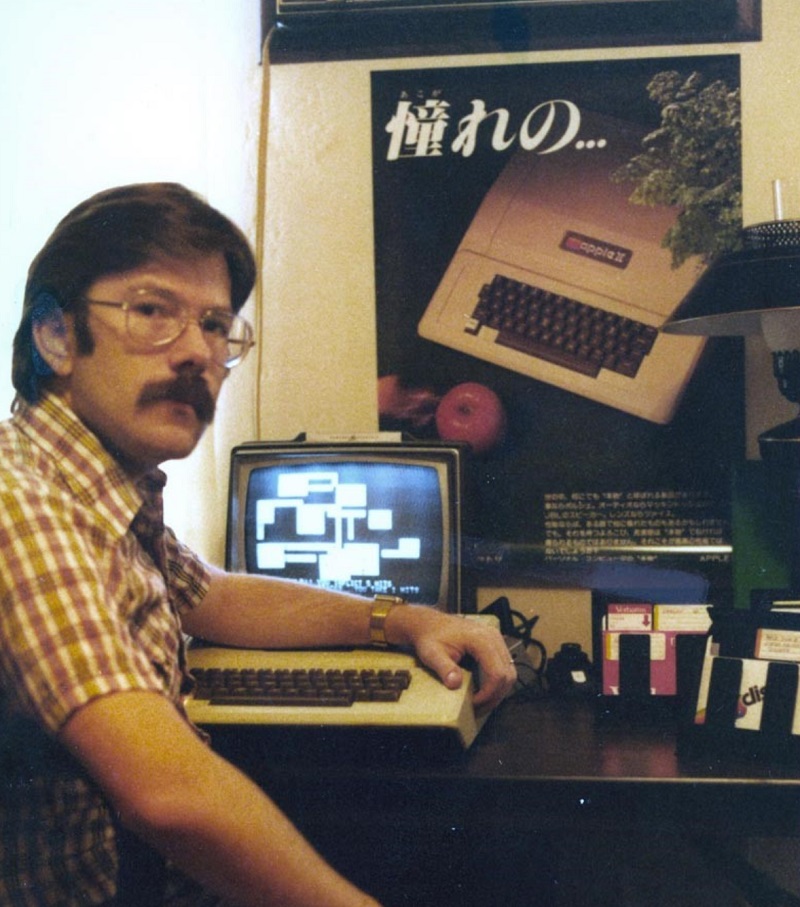

In 1978, Worth and a friend split the cost of an Apple II computer. Hashing out a deal analogous to a custody agreement, Worth got to keep the computer for two weeks before turning it over to his friend for another fortnight. Worth spent his computing time learning Integer BASIC, a language crafted by Apple engineer Steve Wozniak and a staple available on all Apple II machines. Naturally, his inclination was to write a computer simulation of Dungeons & Dragons.

The concept Worth laid out for his game was simple. Players would create an adventurer and explore dungeons inhabited by fearsome creatures that guarded magical artifacts. In RPG parlance, the game would be a dungeon hack, an adventure focused purely on fighting and plundering.

Subscribe to our newsletter!Get Tabletop, RPG & Pop Culture news delivered directly to your inbox.By subscribing you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

And here we get once more into exploration–which is the secret sauce that drives any good D&D game (or really anything else). We’re constantly on the lookout for something that makes us be utterly present in the here and now–in a video game you can have the experience of exploring another world and wondering what lies over the next hill to distract you from the fact that you aren’t necessarily sure what you’re doing with yourself, or if that taco meat was really vegan–and with a roleplaying game, it really comes alive in those moments where you wait to find out what happens next. And BAM is all about what happens next:

He imported abilities and rules that he and his friends employed in their D&D campaigns—listening at doors to detect noise and movement within, breaking down a door, and casting an x-ray spell to reveal the level map. Play proceeded according to turns: first players moved, and then the monsters took a turn, and so on, affording players limitless time to mull over each action.

AdvertisementWorth also tried his hand at writing algorithms that drew brand new levels every time players sat down to the game. To Worth and his friends, part of the fun of Dungeons & Dragons was coming across strange new places. They never knew what dangers might lie in wait around the next turn, which blanketed BAM in suspense and trepidation. One cocksure or poorly calculated move and their avatars could be killed off.

That’s right, BAM was one of the first games to use procedural generation, which is all the rage today–and it all comes from those early games of D&D where things like ‘how deep you are beneath the manor’ determined how powerful the monsters were, and how valuable the treasure. And like a good D&D game, there are a lot of house rules. Actions carried with them a certain cost. Your stats like strength and intelligence were used as fuel for attacks, you could become exhausted if you did too much, and might even have to stand still for a while to refill your gauges.

And the whole idea that your character might die at any time was very old school D&D. Alongside BAM, another game sprung up that embodied much of the same elements: Rogue, which gives the genre its name. Rogue might not have been the first, but it is one of the most enduring. Rogue sends players deep into an epic dungeon in search of the famed amulet of Yendor, looking for treasures that can help them, unearthing new levels of a dungeon and new monsters with each playthrough. Heavily inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure and Dungeons & Dragons, Rogue would go on to inspire a generation of copycats and descendants.

But as Rogue becomes more and more popular, it carves out a niche for itself entirely and veers into its own eccentricities. Though D&D continues to be a huge part of that inspiration, we can leave Rogue to go its own way in the eighties–because around the same time, another D&D-inspired game is coming up.

That’s right, it’s Ultima time. Created by Richard “Lord British” Garriott for the Apple II, the Ultima series has left a huge mark on the world of gaming. Though the story of Ultima actually starts with an earlier world: Akalabeth, which grew up out of Richard “I’m Rich Enough To Have Traveled Into Space” Garriott’s love of fantasy role-playing:

My interest in fantasy role-playing started in high school, about the same time I got interested in computer. My freshman year in high school, I took the one computer programming class the school offered. The school had a Teletype tied in with some computer off in never-never land. And that was the same time I was exposed to the game Dungeons and Dragons, and also the time when I first read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

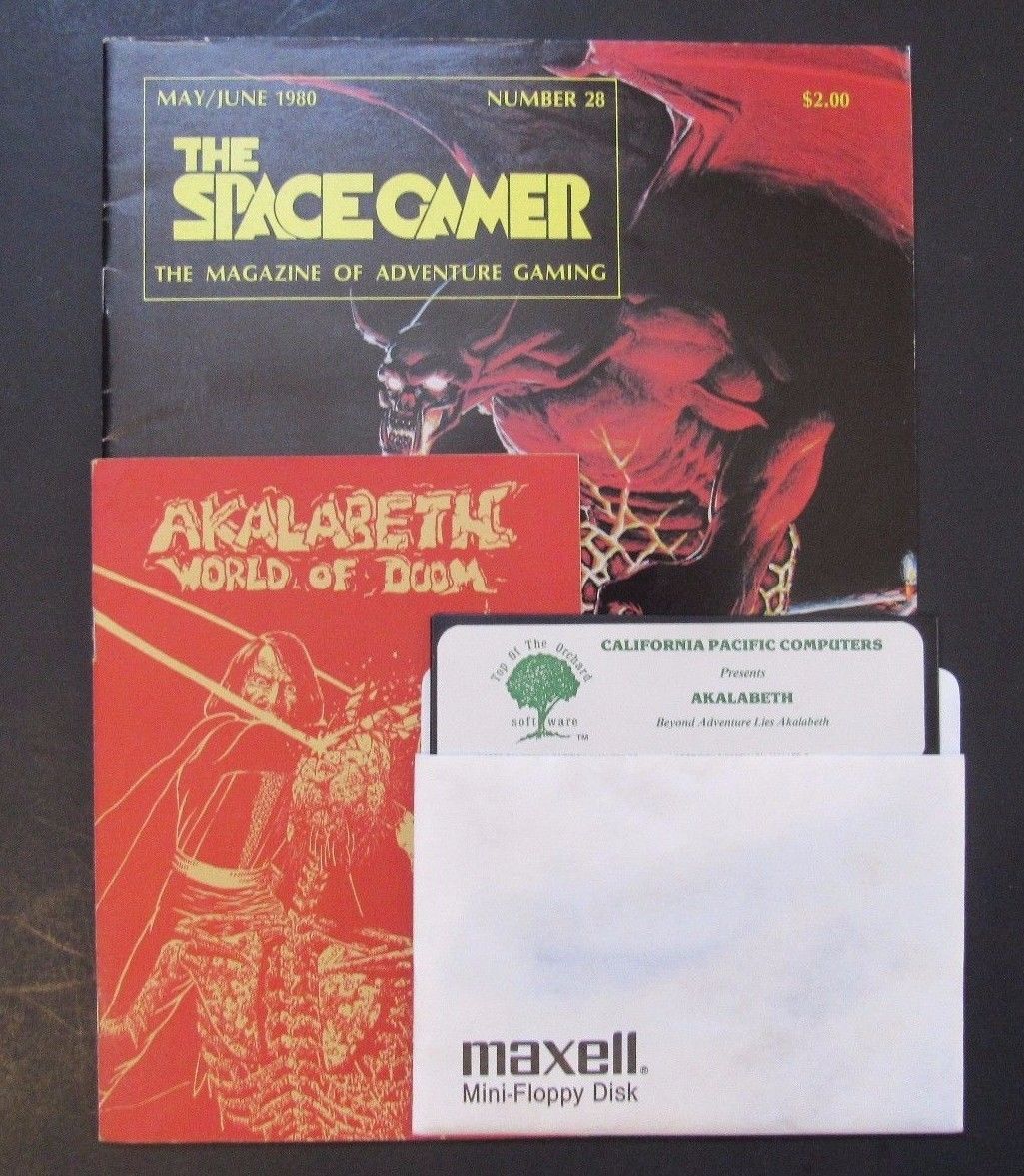

I wanted to write a 3-D high-resolution dungeons game. I took one of my high school games and rewrote it for the Apple. I called the game Akalabeth.

Akalabeth was the end result of a game he’d been working on for several years with a working title D&D28b, which refers to the revision of the game by the time his boss at a CompuerLand in Clear Lake City suggested he sell the game in the store. It traveled from Texas to California, where it attracted the attention of the California Pacific Computer Company, who reached out to Richard “You Wouldn’t Be Surprised If It Turned Out I Once Hunted A Man” Garriott:

The Game ended up at a publisher called California Pacific, who was at the time publisher for Bill Budge, who was at the time the computer game author.

California Pacific looked at Akalabeth, sent me the plane tickets, and gave me a contract. Akalabeth was very well received.

AdvertisementIt didn’t really occur to me until after the game’s success that it had never really been intended for the public. It was an exercise. That’s when I sat down and started over, with the advantage of a friend who helped me with machine language, which I was just learning.

And nine months after that, Ultima was published. Many of the elements in Akalabeth are present in the first Ultima game as well. But Ultima really shook things up for the game industry, establishing a lot of things that, once again seem pretty common these days. Things like the game coming in a box, featuring a cloth map, and having way too many booklets got their start with Ultima. As Garriott puts it:

My games were different. They took over a year to develop. I was more personally tied to how I wanted my games presented to the public […] I wanted my games in a box. I wanted a cloth map. I wanted significant quantities of documentation. But when I told the companies that, about half of them immediately dropped out.

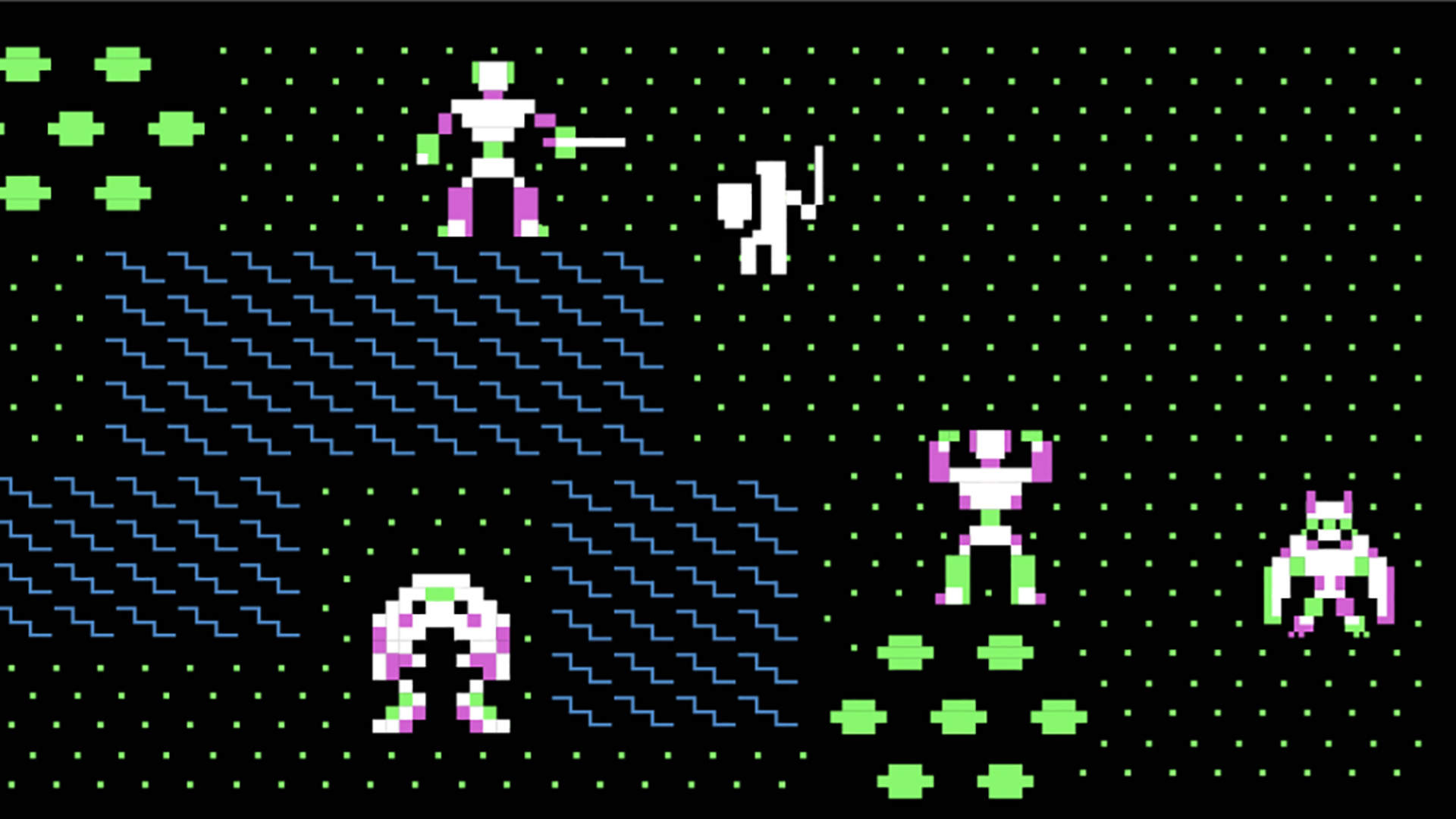

And in Ultima, we see the beginning of computer roleplaying games as we know them today. Games like Baldur’s Gate or Wasteland or Fallout owe their existence to innovations and tropes explored and established in the Ultima series. Simple things like tiled graphics, which allowed the software to generate an entire world with enough detail for relatively cheap, resources-wise. That’s why Ultima has such a distinctive, colorful look. It also was thematically a little all over the place, owing to Garriott’s interest in fantasy and sci-fi:

At the time, the game was hailed for its immense size and “evolutionary” aspect–players started off in the Middle Ages, but later traveled through time. What other game started with daggers and leather and ended up with blasters and spaceships? It was truly an ambitious game. The game also abandoned the “parser” control scheme of Akalabeth and was played by simple keystrokes like Apshai. The game even features some arcade space combat action!

The storyline is related very much to Akalabeth’s, and features many of the same characters. The player’s mission is to seek out and destroy the evil wizard Mondain’s “gem of power,” which he’s used to enslave the lands of Sosaria. However, Ultima is a much more sophisticated game than its predecessor, and players soon learned the values of creative gameplay. For instance, players could steal powerful items from the shops that would make them nearly invulnerable–at least at the early stages of the game. Of course, successful thieving might require a few reloads, but for frustrated players, it was a price worth paying.

Ultima I might have been a little all over the place with its story and theme, but don’t worry Ultima II is hot on its heels and establishes another trope we’re all still familiar with today: it was riddled with bugs. This is reflective of an imminent Exodus from Garriott’s relationship with publisher Sierra On-Line, which came about with the third game in the series, and the one that would leave the biggest mark on the games industry.

Proving that the third time’s the charm (not counting Akalabeth), Ultima III: Exodus strove to capture the sensation of playing a massive tabletop game. It featured a massive open-world map, the land of Sosaria, where you could explore a vast continent surrounded by huge islands filled with cities and dungeons. Players could travel wherever they wanted, barred only by the difficulty of the monsters that they might encounter. Again–there’s that element of exploration that keeps popping back up in the most successful games. We constantly want to find what’s new, what’s around the corner.

And in Exodus, gamers found a whole world to explore, both in terms of the game world and the characters present in the game. Instead of controlling a single character, as you did in the first two games, Exodus put players in charge of a party of four characters–for that true tabletop feel–and featured combat that depended more on location and positioning than just having the biggest attacks. But, as with many good RPGs, combat is only a part of the puzzle. The rest is character and story and in this case, literal, actual puzzles:

My very first games were just ‘go fight stuff, [b]ut that was really just a side effect of my learning how to program. Almost immediately, Ultima became filled with characters that immediately had conversations.

While duking it out with the bad guys factored heavily into Exodus, Garriott invested far more time into developing the realm of Sosaria than he had the previous games’ worlds. There were more opportunities to interact with non-player characters, and the enigmatic structure of the world demanded players explore, observe, and interact. Mysterious devices called Moon Gates appeared throughout the land. By experimenting with the gates, players would eventually learn that they served as teleporters, with the current phase of Sosaria’s twin moons determining the activation of each of gate. Likewise, the battle with final boss Exodus required more than mere dungeon-diving and damage output; success in Exodus requires a fair amount of clue-hunting and puzzle-solving.

And though this still doesn’t perfectly replicate the full picture of a tabletop campaign, which is what Garriott had hoped to do–Exodus was a huge step forward. It’s widely hailed as one of the most influential games of all time, and you can see that in its reach. Exodus’ design is a huge inspiration for an entire generation of European and Japanese designers. You really can feel it in some of the earliest JRPGs, Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy.

Dragon Quest is one of the most popular video game series out there and has been going strong with a hotly anticipated game coming out later this year. And yet, it too has its roots in D&D and especially Ultima: Exodus and Wizardry. It combined the overland movement of Ultima with the random battles of Wizardry and would go on to take Japan by storm. The fact that you can still play a Dragon Quest today, and that it’s still something that fans of the series are looking forward to, should speak to its popularity. But it all starts with the first game (you might have seen it in America originally released as Dragon Warrior). It’s a fairly simple outing: you play a young hero who sets out to defeat the powerful being known as the Dragonlord.

The Dragonlord is a powerful warrior who was once a hermit who shunned the magical radiance of a sacred artifact known as the Ball of Light, which helped maintain peace and prosperity in the kingdom of Alefgard. However, at one point the Dragonlord descends on the castle and takes the Ball of Light, and as a result, monsters creep out onto the world map, and you take up arms as a hero who has arrived to rescue a princess, find the Ball of Light and collect some relics in order to save the day.

But Dragon Quest was a huge breakout hit at the time. There are a lot of elements that went into the game–including an incredible soundtrack, a focus on exploration (once again), and artwork by the legendary Akira Toriyama, of Dragon Ball and everything else fame. It single-handedly invented the JRPG subgenre–if you’re familiar with the whole fight/run/item/spell menu, that all starts here. It also hit at a time when Japan was seeing a resurgence of an interest in fantasy and role-playing games in general. And that’s where we tie back into sword-and-sorcery novels.

The same year that Dragon Quest came out, 1986, also saw the rise of a new genre of storytelling, the “replay” which is basically a transcript of an RPG session–a bit like the one you’re familiar with if you’ve ever read the example of play section in a traditional RPG book. Only these are campaign-length and include everything from table-talk to in-character dialogue. The first of these is The Record of Lodoss War, which is a Dungeons & Dragons “replay” that ran in Comptiq magazine from 1986-1988. It went on to become a popular Anime, and basically started a whole other genre, the Replay–which is fascinating, but that’s a whole other article. For now, all you need to know is that these fantasy novels come about as the result of people really getting into D&D.

And because of that, they were ready to quest all over Dragon Quest. And seeing the smash success of Enix’ Dragon Quest, rival company Square (and ironically now they’re Square-Enix), published the very first Final Fantasy game a year later. As designer Akitoshi Kawazu puts it:

Initially, talking about the genesis of the whole Final Fantasy franchise… [Hironobu] Sakaguchi said, with the first one, “Let’s make an RPG.” I’m a little foggy on just how much Dragon Quest influenced that decision, but the one thing you can say for certain was that when Dragon Quest came out, it proved to this country that RPGs could sell. Mr. Sakaguchi had wanted to make an RPG long before that, but he couldn’t get permission from the company, because the company said, “Well, we’re not sure that will sell.” But with Dragon Quest proving that a game like that could be successful, we were finally able to get that going. It all started with that.

We were all big fans of Wizardry and Ultima back then. Even though Dragon Quest had come out, in our minds, there still wasn’t anything quite comparable to Ultima or Wizardry. That’s the kind of game that Sakaguchi and Hiromichi Tanaka and I were interested in. As far as my role in the game went, I was mainly in charge of the battle system and battle sequences. For that, I tried to make it as close to Dungeons & Dragons as possible. That was my goal.

I didn’t need to oversimplify things, but there are certain precepts when it comes to a Dungeons & Dragons type of environment, a western role-playing experience. Like “zombies are weak against fire,” or “monsters made of fire are weak against ice.” If you think about it a little, they all make sense, and these are all things that D&D already sets up. Certain things are weak against certain other things and strong against yet other things. They all have these relationships. Up until that point, Japanese RPGs were ignoring all of that. They didn’t incorporate those elements. It just wasn’t a part of what they were doing. That’s what I found kind of irritating. Simple as it may sound, that’s the kind of stuff I wanted to work in. Obviously it’s going to be hard to simulate the human experience of a game master and the players interacting. I couldn’t be too worried about that kind of thing. But I did want to incorporate those precepts of western RPGs into the game.

Ironically, the whole thing eventually wends its way back, with games like Final Fantasy influencing later game designers, who would go on to design the games that influenced later editions of D&D, but that is a story for another time. Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest took the concept of RPGs and ran with it in their own direction, while back in America, D&D entered into its first big turmoil. With the rise of 2nd Edition, a whole new wave of games was on the horizon.

But that’s a tale for another time.

Happy Adventuring!