That Time TSR Sued The Internet Over Dungeons & Dragons – Prime

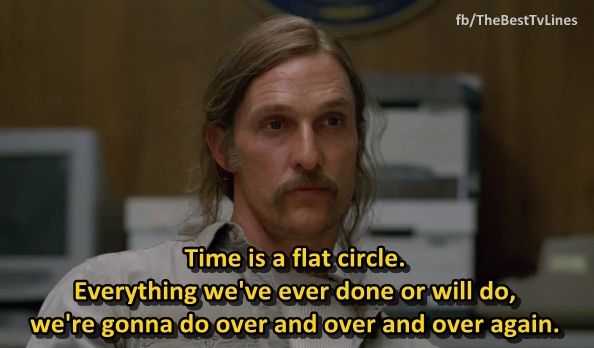

In the magical year of 1994, Ravenloft debuted as a campaign set but the real horror was that TSR sued the whole entire internet.

The internet is a wild place, but back in the early days of its creation in the years between when the oceans drank Atlantis and the rise of the sons of Aryas, it was an age undreamed of when it seemed like anything could happen. Including the events of both Hackers and The Net, which are two movies that addressed the burgeoning new technology.

But you don’t have to be in Hollywood to not understand how computers work. You could also be a lawsuit-happy roleplaying game publisher who caught a whiff that files might be stored somewhere, which is how in 1994, the TSR came to sue most of their fans on the internet, wherever they could find them. Grab your TMNT backpack and step back to 1994 with us as we look at the time that TSR sued the internet.

The year was 1994, and TSR had built up to be something of a money-hungry, loose-cannon with legal regards entity. People called them T$R or would say the initials stood for “They Sue Regularly” and with good cause. By the time we get here, TSR has been embroiled in several legal battles against other RPG publishers, especially ones that employed/were founded by the now-exiled creator of D&D, Gary Gygax.

It was a well-earned reputation, and soon you’ll see why. First though, we need to talk about what fans of D&D at the time were doing. In those days, fan-sites were a huge thing, if you can believe it.

Anyone with a modem and knowledge of Webrings or USENET could share their interests with anyone and everyone. As you might imagine, Furries, Furry Art, and Furry “Art” was everywhere, but though that would make up the bulk of the early internet, a lesser-but-still-significant volume of bandwidth was dedicated to D&D. People shared all sorts of creations with one another, because if there’s one thing that people love it’s sharing their own homebrewed content.

You could find sites that had everything from ftp sites that had scanned copies of the books, to adventures written and set in worlds like Greyhawk or the Forgotten Realms, new monsters, new spells, new classes–and if that sounds like exactly what people are still doing today, you’d be right.

And as many fans put it, this was one of the best ways for people to discover the game or rejuvenate their own interest in the game. As Trent A. Fisher puts it:

Sometime around 1988, I discovered rec.games.frp and related newsgroups on USENET. This changed everything for me, suddenly I was reading details of other people’s games, alternate rules, monsters, maps, stories, etc. This cross-pollination greatly improved my own game and rejuvenated my interest. I started buying material for the new Forgotten Realms setting and started a campaign based on it.

Within a couple of years, my university got connected to the internet, and we set up an ftp server on a Tektronix workstation sitting in the computer science lab (on more than one occasion the FTP site was down because a student bumped the network equipment behind that machine). One of the first things I did was start collecting the useful bits from rec.games.frp and populating my ftp site. On 10-Apr-90 I sent an announcement to rec.games.frp, and even more things started coming in and the site grew by leaps and bounds.

Advertisement

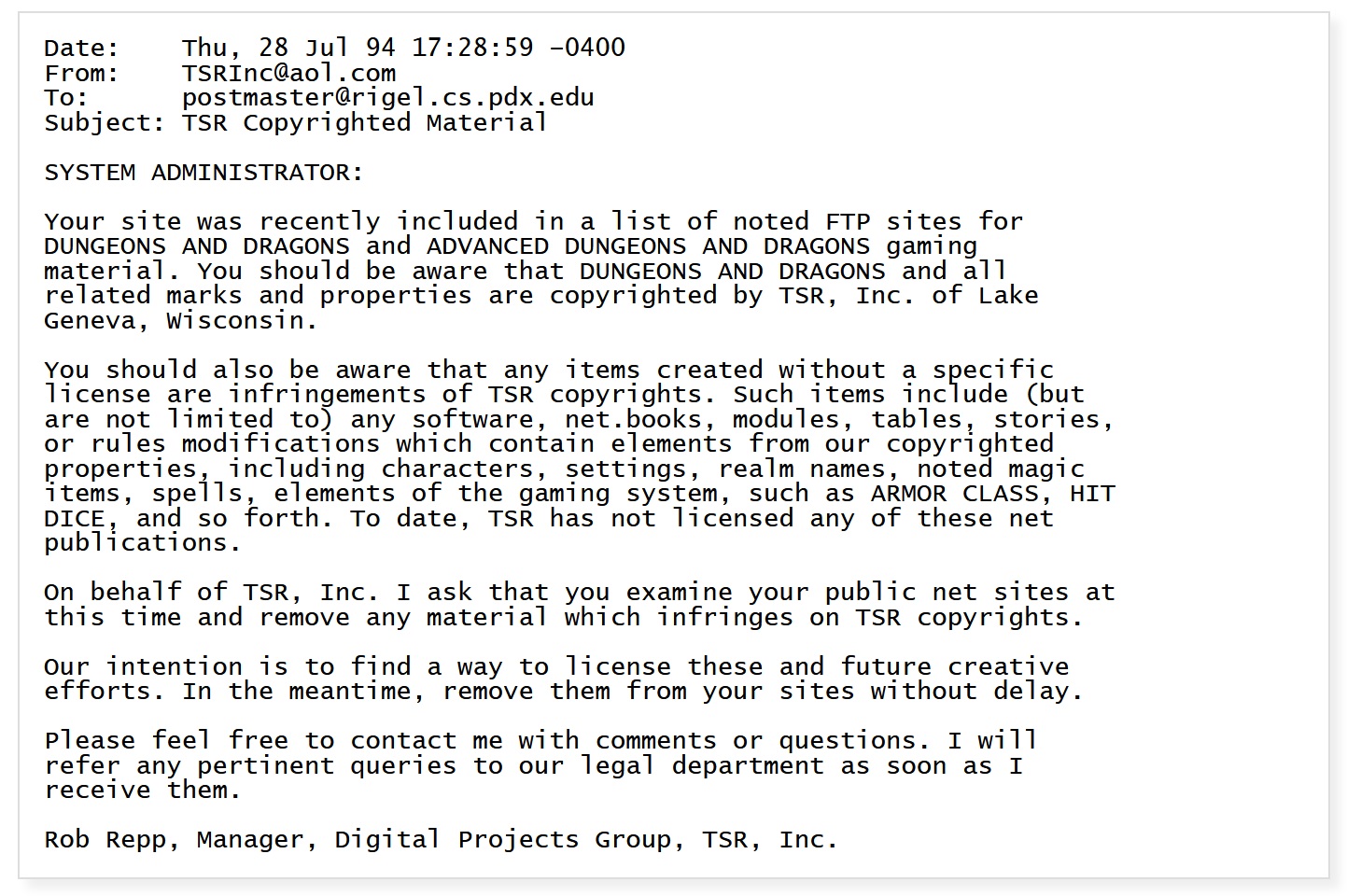

Then in 1994, Fisher–along with many others received an email from Rob Repp, TSR’s newly hired head of Digital Projects:

Now there’s a lot to unpack here, not the least of which is that TSR tried to claim as part of its copyright “characters, settings, realm names, noted magic items, spells, ARMOR CLASS, HIT DICE” and more as part of their own copyright. If any of this sounds like a similar lawsuit by Games Workshop, then you know how this story ends.

And ftp sites were far from the only ones hit with this notice. Noted D&D historian Shannon Appelcline, then-administrator of a Berkeley University fan-site that mostly served as a repository for Ars Magica was hit with the same notice. It seems like everyone who operated anything roleplaying game related online was TSR’s target. As Appelcline puts it, he was less than impressed:

“Overall if you think about the Internet at that time being focused on [educational domains], you can see that you had a lot of anti-establishment people on the Internet and so none of us liked TSR that much. Everyone wrote T$R for example. Now they’re sending these nasty letters for legal rights that they probably don’t have. The letter I wrote [in response] said, ‘Not only do we not have any files related to D&D on our site, but we never would. I would rather poke my eye out with a stick before doing anything to help you.’ That phrase was genuinely absolutely, in the letter.”

Little wonder that later, when TSR was absorbed by WotC, one of the biggest lessons learned was that TSR had no way to tell what it’s audience wanted. If only TSR had taken to heart what they put in the Dungeon Master’s Guides–when you have a problem, try talking it out at your table before resorting to rules lawyering.