The Stars Are Right For A Look At The Call Of Cthulhu’s History – PRIME

Dungeons & Dragons invented RPGs, but Call of Cthulhu changed the way we think of them forever. The stars are right, let’s take a look.

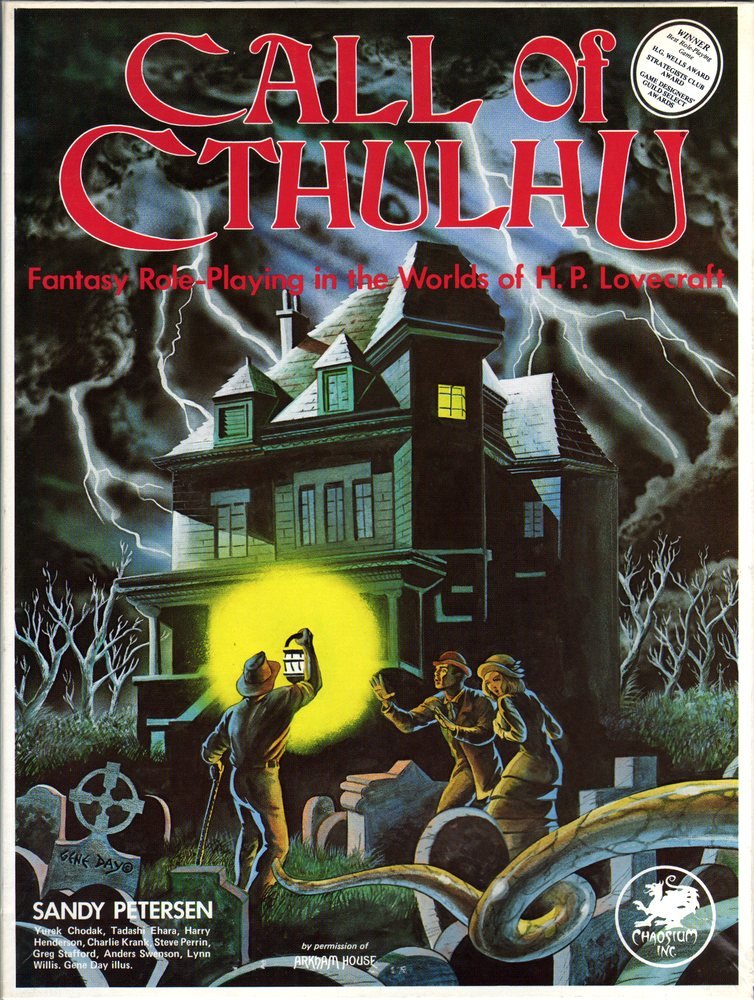

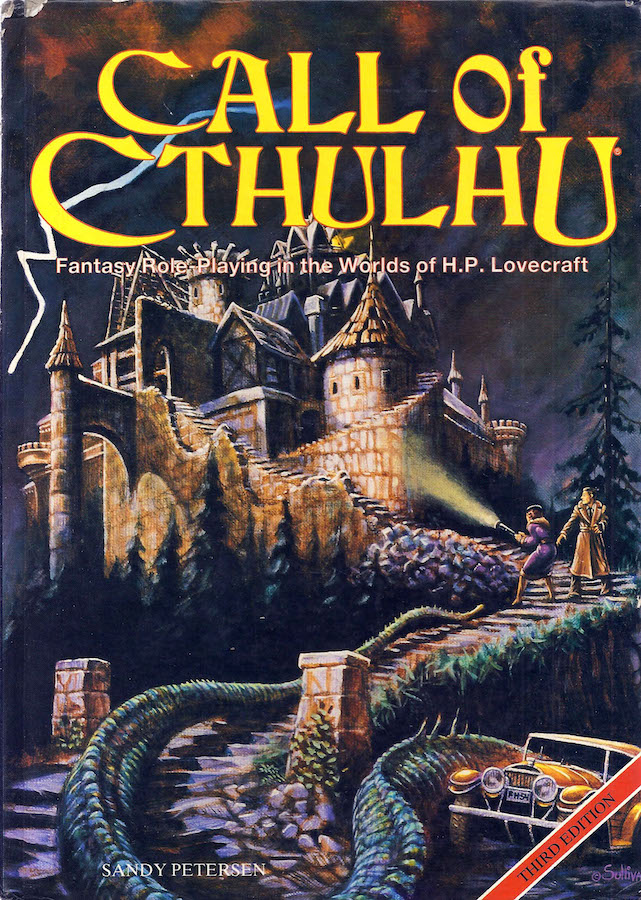

When something is iconic, it carries a certain metaphorical weight to it. When you hear D&D, even if you’ve never played the game, you can imagine anachronistic fantasy heroes battling monsters and finding treasure. Just like when you hear Call of Cthulhu, you probably picture investigators in a vaguely 1920s atmosphere, poring through eldritch tomes, or, depending on your style, a whole lot of dynamite. And there’s a reason that Call of Cthulhu is so iconic–to the point that it eclipsed the other big releases in 1981, when it launched. That’s because Call of Cthulhu changed roleplaying games forever. So come join me as we wait for the dread stars to align in the sky, and let us consult the unspeakable tomes of lost history as we look at the rise of Call of Cthulhu.

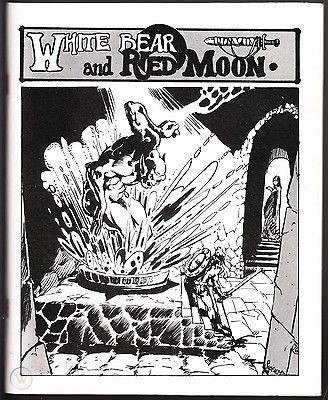

Call of Cthulhu was not the first of many things–it wasn’t the first RPG, it wasn’t the first licensed RPG (that goes to either Star Trek or Dallas, depending on who you ask), it wasn’t the first RPG to let the tides turn against players, often in dramatic fashion, but what it does, it does exceedingly well. And it’s all thanks to the environment it began in. And that begins in 1975, in Oakland, California, where a man had “an auspicious reading of Tarot cards” and decided to begin his own company to publish a game called White Bear and Red Moon.

That man was Greg Stafford, founder of the company originally known as The Chaosium (though in later years, they’ve dropped their ‘the’), creating a portmanteau of chaos and the Oakland Coliseum, near his home at the time. The Chaosium began in an effort to publish a game that Stafford had created to combine his love of both fantasy and gaming, giving folks the tools to create a “do-it-yourself” novel in the form of a board/wargame set in Stafford’s world of Glorantha. But even this game, which is a “wargame” in format only, already starts deviating from the traditional idea of a wargame. Hailed as one of the best fantasy games published, White Bear and Red Moon broke boundaries, bringing what critics called a “sense of the Literary” to fantasy wargames.

According to no less an authority than J.R.R. Tolkien: ‘To make a Secondary World inside which a green sun will be credible, commanding Secondary Belief, will proabbly require labor and thought, and will certainly demand a special skill, a kind of elvish craft. Few attempt such difficult tasks. But when they are attempted and in any degree accomplished then we have a rare achievement of Art, indeed narrative art, storymaking in its primary and most potent mode.

In the world of WB&RM there is no green sun (as far as we yet know) but there is certainly a red moon. This red moon exerts omnipresent, inescapable effects on every other aspect of Dragon Pass. It does so by a means no more visible than the Earth attracts an apple, but it performs its magical functions just as inexorably.

AdvertisementI have seen other fantasy games which try to throw in any number of ideas as pure atmospheric devices into their backgrounding scenarios. These devices exist only as window dressing, they are useless, they are absurd as they have no function. The awesome red moon has a function, and that function weaves throughout the mythos of Dragon Pass … it is more, much more, than mere atmospheric trapping. In the game … it is not only a mood setter, it is a raison d’etre, upon its presence hinges many other facets of the entire subcreation.

This comes from an in-depth look at the world of Dragon Pass situated in Glorantha, Stafford’s own fantasy setting. His ideas of themes and narrative having a substantive effect on the game were among the core ethos of Chaosium’s work. White Bear and Red Moon was a hit among the crowds it could reach, quickly taking Chaosium into the games industry. Though for the first few years, it was all board games, mostly along wargames lines until 1977 when Chaosium started publishing roleplaying games. Here and there they would work on developing games with TSR, and are one of the first games to legally use any of TSR’s stuff, owing to an interesting hitch with the license for HP Lovecraft’s stories.

The plot thickens. And doubly so when you look at why it thickens. In order to do that, it comes down to Deities and Demigods–but Deities and Demigods wouldn’t come about without Chaosium’s influence on RPGs. RuneQuest, the big Gloranthan RPG, introduced some key concepts to the industry:

It was the first game to introduce a fully skill-based character system. Traveller previously introduced skills to the roleplaying mainstream,, but with two major caveats. First, initial skills were limited to what was available in a character’s class/career. Second, there was no experience system. RuneQuest resolved both of these issues.

AdvertisementIt offered up one of the earliest deeply detailed fantasy worlds. This was an emerging trend in roleplaying.

It was the earliest serious look at religion in RPGs. Before that, clerics had been present, but their religion was mostly glossed over. Even Gods, Demi-Gods, and Heroes treated deities more as monsters than important cultural forces.

As you can see, theme and story are important to Chaosium. Without that fertile ground, Call of Cthulhu might otherwise just have been another hack-and-slash game that was little more than window dressing over a wargame. You have to remember, this is all happening around the same time that D&D is coalescing into its very 1st Edition, and AD&D is definitely taking some cues from the competition, as well as pushing the industry space in its own direction. It’s interesting to wonder what the face of gaming would be like if RuneQuest had been the game that caught the public eye and gone on to grab the same market/audience that Dungeons & Dragons has garnered over its forty+ year history, but, for now Chaosium’s influence spreads into the games industry as they pull together some highly unlikely books.

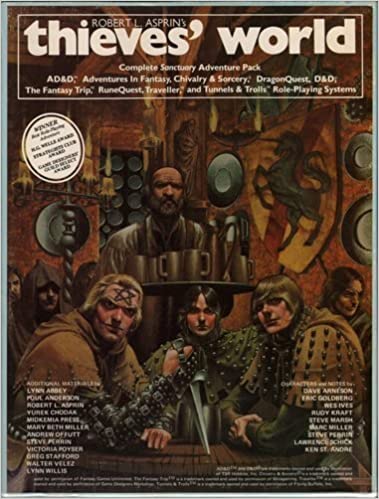

Which brings us to the creation of Deities and Demigods–at the time TSR is developing this book, Chaosium has the license to HP Lovecraft’s work, as well as Michael Moorecock’s world of Melnibone (used in their game Stormbringer). They leverage their licensing rights, agreeing to let TSR use them in exchange for using their own work to create a massive supplement called Thieves’ World, based on Robert Aspirin’s shared-world fantasy series by the same name. And in the same vein, this was a shared-system supplement, by Stafford’s design it was meant to be as collaborative as the books that inspired it, which meant that Thieves’ World came with rules for AD&D, Adventures in Fantasy, Chivalry and Sorcery, DragonQuest, RuneQuest, Traveller, and more.

For today’s comparison that would be like someone putting out an adventure module designed to be run in D&D, Pathfinder, Starfinder, Torchbearer, Dungeon World, and Blades in the Dark. It’s not impossible, but it takes a certain kind of vision. Thieves’ World debuted in 1981, pushing the launch of Chaosium’s ‘lesser’ game, based on Lovecraft’s mythos, to a late release that same year. That’s how out of nowhere Call of Cthulhu was when it came crashing onto the scene. Its release had been delayed, twice, for “more important” books, missing Origins and Gen Con, but in November of 1981, Call of Cthulhu finally released and gaming was changed. We can see how important it’s become since then, but at the time, this was a huge experiment for Chaosium.

After all, the original developer, Sandy Petersen, had come to Chaosium, pitching them on designing a Lovecraftian RPG for years before they finally accepted. They were working on a different game called Dark Worlds, which fell apart, and so with Petersen working full-time at Chaosium, they gave him the go ahead to create Call of Cthulhu.

It’s hard to overstate how influential Call of Cthulhu has been on the gaming landscape; it’s a lot like Casablanca in a way because it did a lot of things that everyone does now, so it doesn’t seem all that groundbreaking, but then you realize they did a lot of it first. Let’s start with something that seems simple but can still be felt today: shifting role-playing away from hacking and slashing and instead reframing roleplaying to center around investigation and interaction.

Because in Lovecraft’s stories, themes of mystery pervade the mythos. You can’t have a fear of the unknown without having something there to not know about in the first place… you have to understand just enough to draw you further. And with Chaosium’s ethos of theme and narrative having just as much influence, Petersen decided to make investigation and introspection central to the game’s mechanics. As he describes it in an interview with io9:

Most games up till then were combat-centric. Adventures centered on fighting. In the horror genre, the weakest conceivable monster is probably a cultist, who is, by definition, just as tough as an investigator (since they’re both humans). Something like a werewolf or ghost is fierce enough that a whole novel or movie can be plotted around just one.

It was obvious that Call of Cthulhu needed a different focus beyond combat, so I zeroed in on investigation, which also fit Lovecraft’s characters and stories. I basically substituted investigation and research and uncovering of secrets for the combat.

Built on an adaptation of Chaosium’s Basic Roleplaying System, which was the same engine that powered their Glorantha games like RuneQuest, Call of Cthulhu leveraged its streamlined nature to help players “move past the rules, and into the activities.” If you’ve ever played a single session you’re familiar with the basic roleplaying system. But if you’re not, it’s one of the first truly skill based systems–characters aren’t really built off of a class template, but rather from a concept. As it says in the first edition of the book:

Players in Call of Cthulhu take the part of intrepid investigators of the unknown, attempting to ferret out, understand, and eventually destroy the horrors, mysteries, and secrets of the Cthulhu mythos. A game moderator, known as the Keeper of Arcvane Lore is necessary for this game, and his role is to attempt (within the rules of the game) to set up situations for the players to confront.

The players … have a duty to play their investigators within the known limits of the characters they run. Remaining unbiased is as difficult for the players as for the referee. Just because a player is a science major and knows how to concoct subtle and potent compounds does not mean that his 1922 New York street cop character (without learning or training) could stroll to Yonkers and set up a pharmacy.

Advertisement

And by and large the game puts you on track to do exactly that. You can create your character around a fairly free-form concept, because characters in this system are by and large, a lot more streamlined than other counterparts. You have characteristics and skill rolls and that’s about it. Unlike D&D there are nine basic stats, though again we see D&D’s influence in their naming conventions. We have: Strength, Constitution, Dexterity, Power (or Willpower), Size, Intelligence, Appearance, Education, and Sanity.

And on this last stat, a whole concept was founded. Let’s leave aside character creation for now and turn a corner to see what unspeakable horrors lie in await for us when we talk about Sanity. Themes throughout Lovecraft’s work revolved around various arcane/eldritch truths driving those who learn them into madness, whether from the sheer horror of learning how small and insignificant they are compared to a cosmos that, far from empty, is teeming with horrors to whom humanity is merely an insect–or whose fear of the unknown/the corrupting influence of Elder Things drives into a frenzy. And Petersen wanted to capture that feeling, so he introduced a sort of mental landscape to the game.

In Call of Cthulhu, investigators not only risk bodily harm, but they risk mental trauma as they confront the horrors of the mythos. Investigators lose points of sanity as they gain Cthulhu Mythos knowledge as well, meaning that the further they go, and the more they learn about their foes, the more Investigators risk not only their lives, but their selves as well. You might stop a powerful cult from summoning an Eldritch Horror into the world, but at what cost? What sort of sacrifice are you willing to make to stop the rise of something like Cthulhu?

As we said, Chaosium does theme and narrative better than pretty much anyone else. They tie the feeling of the game to the mechanics, so you can’t help but be transported. So while you’re playing a cop or a professor, the system is pointed, every way it can, into making you feel like you’re just a cop or a librarian who learned the wrong thing. A big part of this is that in the game, characters can improve–but it’s mostly in the things they know, or in the likelihood it is that they’ll accomplish something. There aren’t levels, per se, just experience points that you gain for doing things in the world. You can spend those points to improve your skills, and since the whole game is based off of a percentile system, you have a pretty immediate measure of how much more skilled your character grows as you play. But, and this is key, you don’t grow in power. Not really. You don’t gain hit dice every “level” you don’t suddenly turn a corner and make yourself unkillable.

The system makes characters feel very fleshy, and very vulnerable. It was the opposite of the power fantasy that is D&D–Call of Cthulhu catered to a much different kind of fantasy. It wanted to deliver the experience of horror to its players, and in order to do that, it needed to have levers that it could use against the characters. And it doesn’t matter how skilled or tough you are, Cthulhu can sitll show up and it’s going to be bad. Which is why there are so many Call of Cthulhu stories that end with a bus full of dynamite and stories of collateral damage.

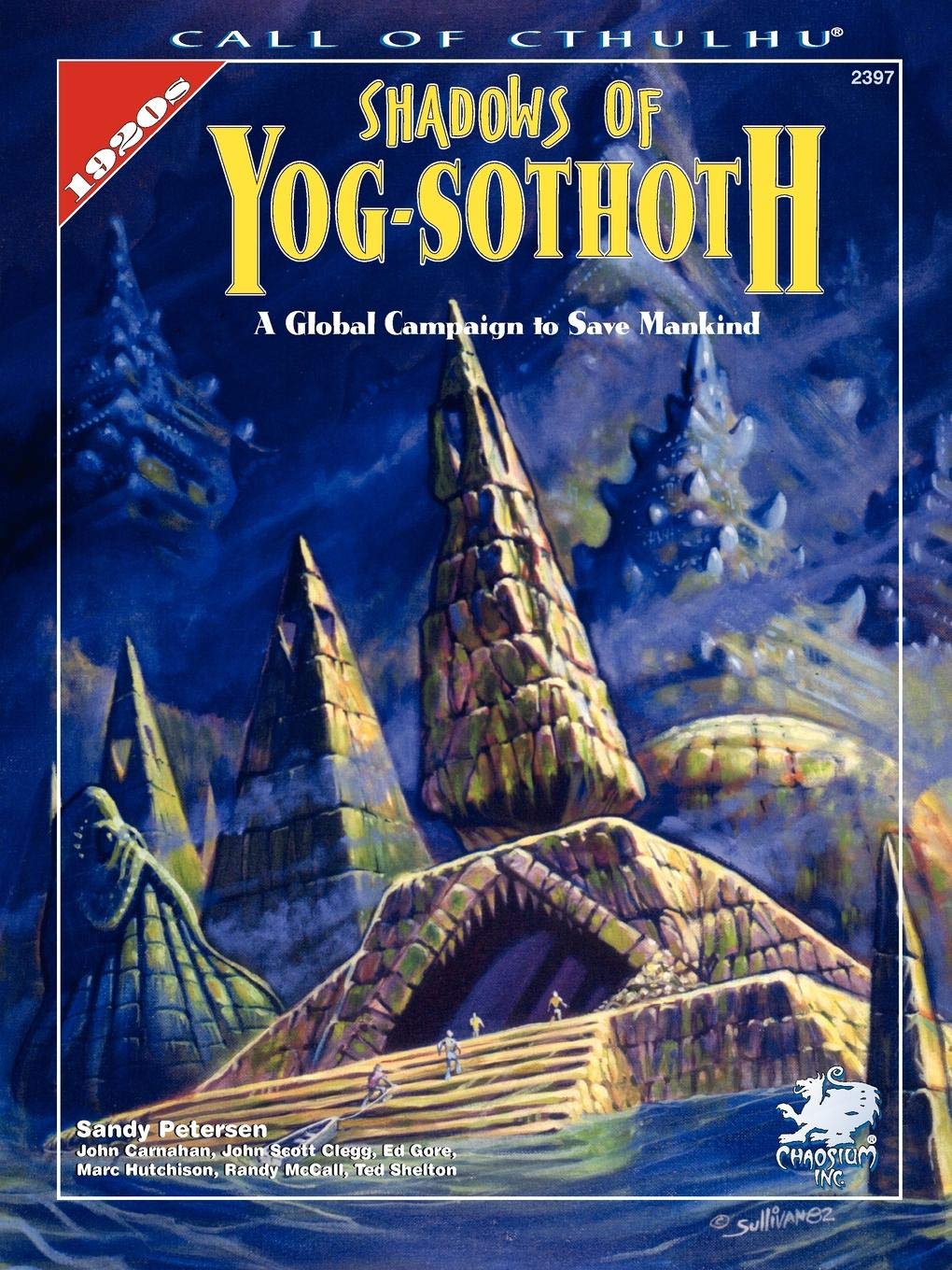

But this focus on immersion doesn’t stop with the mechanics. Some of the early campaigns for Call of Cthulhu are RPG treasures that hold up to this day. A huge part of that comes from the way they were designed. Let’s take a look at the very first Call of Cthulhu campaign, Shadows of Yog-Sothoth, the very first CoC supplement ever published. It did two things extraordinarily well. Both seem fairly straightforward when you hear about it, but again, this is the first system to really pull it off the way that other games wished they could’ve.

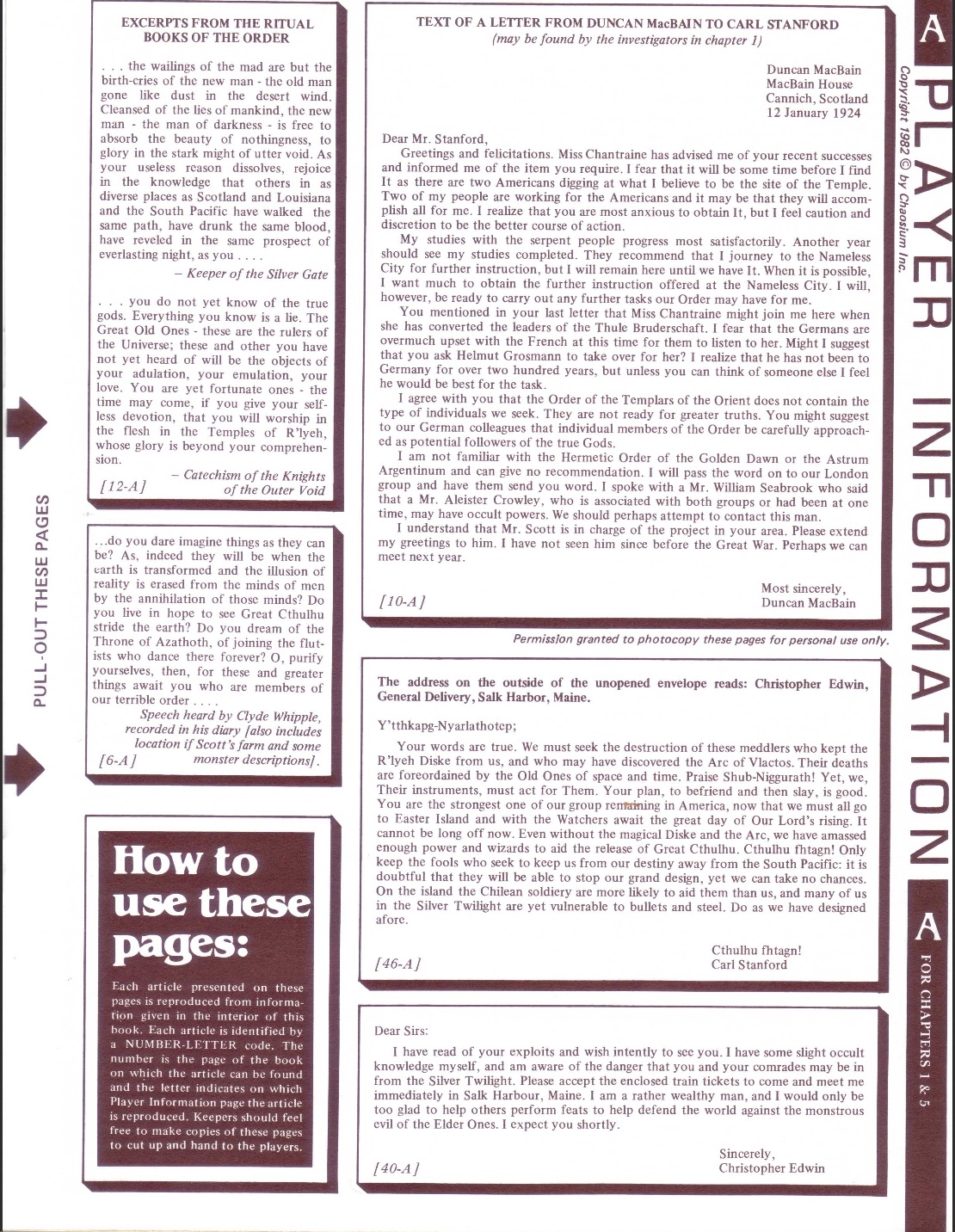

Shadows of Yog-Sothoth took the idea of Roleplay Aids and ran with it, refining player handouts to the point that pretty much every game/adventure has them now. You don’t get to be a major player in the industry and not have player handouts. While D&D might have gotten there first, Cthulhu did it best. One of the first modules to introduce handouts was S1: The Tomb of Horrors, and it had a book of pictures that the DM could show to players. Shadows of Yog-Sothoth, on the other hand, had an eight-page centerfold spread full of information meant to be revealed to the players as they discovered it. Where a D&D illustration might contain a description of the statue that players needed to investigate, Call of Cthulhu wanted to just hand you an actual clue that you could puzzle out. Take a look.

And recall, this is the first time anyone’s doing anything like this in the industry. Call of Cthulhu set the bar high for player supplements. Immersive props and the like that folks like Beadle and Grimm develop owe their existence to this one campaign module that struck a chord that resonates to this day. and they keep on running with it. A few years back there was a Kickstarter for one of the greatest RPG adventures of all time, Masks of Nyarlathotep, and not to reprint it or anything like that, but rather to recreate a “gamer prop set” of all 109 different handouts and props.

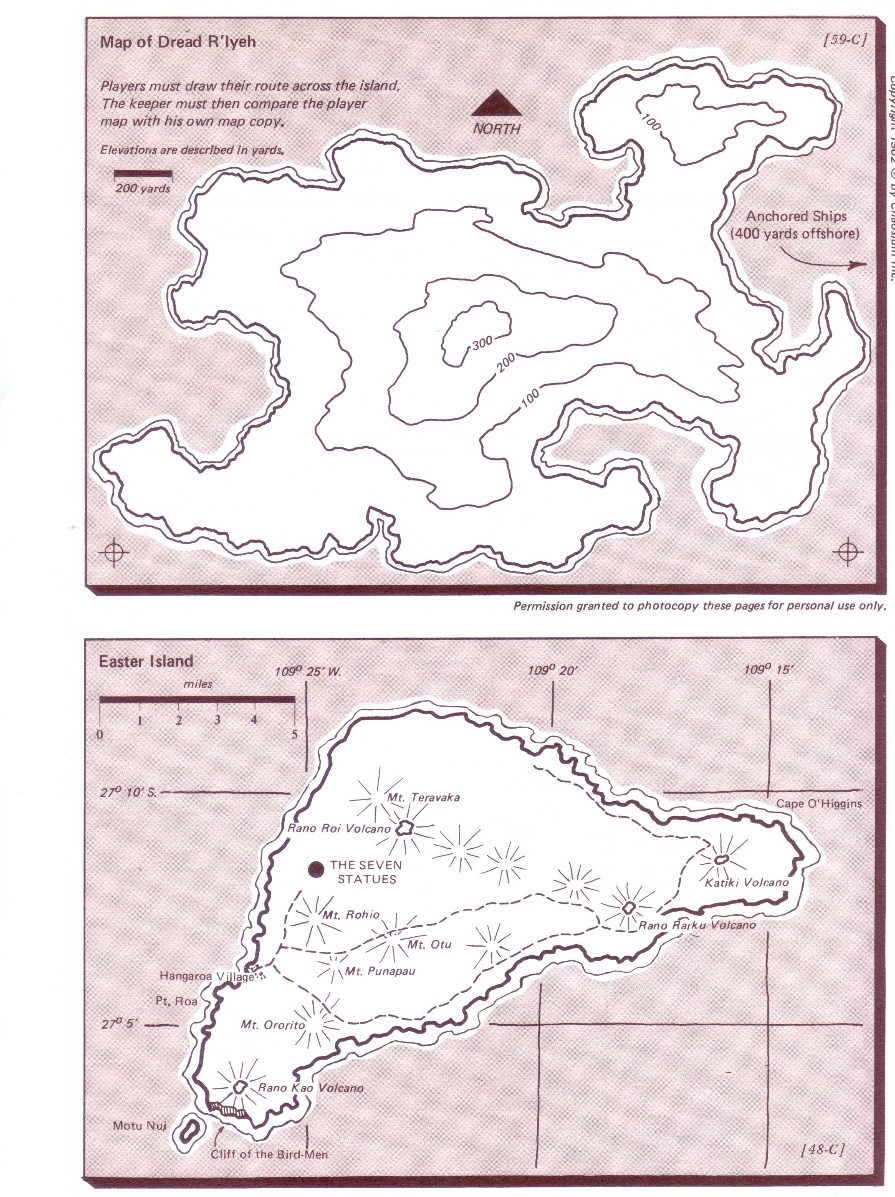

Because there’s a huge difference between being told “you find a letter buried in the professor’s desk” and being given the actual letter that your character has just found. And moreso when that letter contains information that you need to uncover if you’re going to try and stop the cultists who are planning a ritual when the next full moon is upon you in just a few short days. And going back to Yog-Sothoth for a moment, the campaign even includes a section where players must trace their route on an island across a blank map that the GM then compares with a master copy that shows what hazards they might encounter across the way. Players might puzzle out information and then they have to apply it. It appeals not just to characters, but to what the actual players put into the game as they pursue cultists across the globe.

Which brings us to the other big concept that Shadows of Yog-Sothoth laid the groundwork for. Cthulhu stories sprawl in unexpected ways across unlikely paths. A package delivered to a professor’s nephew in a small Massachusetts town might lead to a forgotten ruin in a jungle halfway across the world and a desperate confrontation with a monster that has been hunting human prey and, if left unchecked, might spread its monstrous influence across the world. Or, as happens pretty often in Cthulhu-related video games, something much more mundane-seeming, like a disappearance or a murder, sparks the investigators to tumble well out of their depth, into a world that holds nothing but monsters and darkness and death.

This style of revelation, called the “onion skin” system is meant to convey the investigator’s descent into the world of the mythos. Every layer of reality they know is peeled away. Clues lead not onward, but inward:

The first campaign for Call of Cthulhu, it paved the way for many classics to come and it introduced the concept of the onionskin campaign. This has the investigators stripping away layers of information like the skin of an onion as the players progress through the campaign, revealing more of the evil cult’s plans and coming closer to the heart of the adventure.

In Shadows of Yog-Sothoth, that cult is the Masters of the Silver Twilight, an international organization dedicated to a single aim. Dread Cthulhu sleeps still in the sunken city of R’lyeh yet stirs as the stars converge. Even though the stars are not quite right, the cult believes it can force the premature rise of the city and release the Great old One. The campaign against the cult is broken into seven parts, taking the investigators from Boston to New York, then Scotland, California, Maine, and finally Easter Island and the South Pacific.

Campaigns in Call of Cthulhu followed this model. They refined the ideas included in this campaign, and developed more globe-trotting, secret-laden campaigns that kept players feeling like they were chasing down a dark secret. Culminating in Masks of Nyarlathotep, which is worth a read whatever edition of Cthulhu you’re playing.

But whatever the case, modern gaming wouldn’t be remotely close to what it is without Petersen and Call of Cthulhu. It was the game that finally got RPGs to leave behind their Wargame roots and step fully into a new genre of game. From the first edition to the seventh, you can find some of the best gamemaster and player advice out there in its books. Just be careful–if I’ve learned one thing in my time playing Call of Cthulhu, it’s that reading books gets you killed.

Call of Cthulhu remains a classic today for a reason. How has it influenced your own personal games?